And that reminds me of a little song that I was taught years ago by a trainer in diversity.

Its in every one of us

to be wise.

Find your heart

open up both your eyes.

We call all know everything

without ever knowing why.

Its it every one of us

to be wise.

Another great wisdom of the ages is reported to have been penned by one of our great philosophers of the 20th Century, Reinhold Niebuhr.

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

I've recently been reading up on Niebuhr (but will grant that there are probably many of you who know his writings and teachings better than me), since hearing about a conversation about him between then-Senator Obama and David Brooks back in the spring of 2007.

Out of the blue I asked, “Have you ever read Reinhold Niebuhr?”

Obama’s tone changed. “I love him. He’s one of my favorite philosophers.”

So I asked, What do you take away from him?

“I take away,” Obama answered in a rush of words, “the compelling idea that there’s serious evil in the world, and hardship and pain. And we should be humble and modest in our belief we can eliminate those things. But we shouldn’t use that as an excuse for cynicism and inaction. I take away ... the sense we have to make these efforts knowing they are hard, and not swinging from naïve idealism to bitter realism.”

Niebuhr was a Christian theologian/philosopher who lived from 1892-1971. He began his career as a pastor committed to the social gospel and pacifism. The rise of fascism and the events of WWII caused Niebuhr to question these commitments in a way that holds the tension between "the world as it is" and "the world as we want it to be.' Over the course of the years, it seems that many have adopted what Niebuhr said on one side of this tension or the other. But that, to me, seems to be viewing him with one eye as an escape from the difficulty created by looking at what he said through both.

Interestingly enough, the most cogent description of this tension comes from Wilfred M. McClay who surrounds it with alot of verbiage that I otherwise disregard (how very Niebuhrian!). As someone who doesn't hold to the Christian faith, I find this a powerful statement when I exchange the word "Christian" with "progressive."

Niebuhr dismissed as mere “sentimentality” the progressive hope that the wages of individual sin could be overcome through intelligent social reform, and that America could be transformed in time into a loving fellowship of like-minded comrades, holding hands around the national campfire. Instead, the pursuit of good ends in the arena of national and international politics had to take full and realistic account of the unloveliness of human nature, and the unlovely nature of power. Christians who claimed to want to do good in those arenas had to be willing to get their hands soiled, for existing social relations were held together by coercion, and only counter-coercion could change them. All else was pretense and pipedreams.

This sweeping rejection of the Social Gospel and reaffirmation of the doctrine of original sin did not, however, mean that Niebuhr gave up on the possibility of social reform. On the contrary. Christians were obliged to work actively for progressive social causes and for the realization of Christian social ideals of justice and righteousness. But in doing so they had to abandon their illusions, not least in the way they thought about themselves. The pursuit of social righteousness would, he believed, inexorably involve them in acts of sin and imperfection. Not because the end justifies the means, but because that was simply the way of the world. Even the most surgical action creates collateral damage. But the Christian faith just as inexorably called its adherents to a life of perfect righteousness, a calling that gives no ultimate moral quarter to dirty hands. The result would seem to be a stark contradiction, a call to do the impossible.

I would suspect that anyone who has been on the ground floor of working for social change can recognize the reality of getting your hands soiled in the process of challenging existing social relations that are held together by coercion. The dilemmas of real life don't often fit into the neat categories of "good vs evil" that our verbiage can sometimes embrace. And yet, the "other eye" must always stay focused on the ideal in order to maintain a course towards the love ethic of justice and righteousness. Holding that tension is what we are called to do.

You can hear the echos of Niebuhr in Obama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize.

We must begin by acknowledging the hard truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations -- acting individually or in concert -- will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.

I make this statement mindful of what Martin Luther King Jr. said in this same ceremony years ago: "Violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones." As someone who stands here as a direct consequence of Dr. King's life work, I am living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. I know there's nothing weak -- nothing passive -- nothing naïve -- in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.

But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone. I face the world as it is, and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American people. For make no mistake: Evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler's armies. Negotiations cannot convince al Qaeda's leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism -- it is a recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.<...>

So yes, the instruments of war do have a role to play in preserving the peace. And yet this truth must coexist with another -- that no matter how justified, war promises human tragedy. The soldier's courage and sacrifice is full of glory, expressing devotion to country, to cause, to comrades in arms. But war itself is never glorious, and we must never trumpet it as such.

So part of our challenge is reconciling these two seemingly inreconcilable truths -- that war is sometimes necessary, and war at some level is an expression of human folly.

Obama then spends the last half of his speech identifying the other side of the coin...what we must do to maintain our ideals that lead to peace. He ends with this.

But we do not have to think that human nature is perfect for us to still believe that the human condition can be perfected. We do not have to live in an idealized world to still reach for those ideals that will make it a better place.<...>

For if we lose that faith -- if we dismiss it as silly or naïve; if we divorce it from the decisions that we make on issues of war and peace -- then we lose what's best about humanity. We lose our sense of possibility. We lose our moral compass.<...>

Let us reach for the world that ought to be -- that spark of the divine that still stirs within each of our souls.

Somewhere today, in the here and now, in the world as it is, a soldier sees he's outgunned, but stands firm to keep the peace. Somewhere today, in this world, a young protestor awaits the brutality of her government, but has the courage to march on. Somewhere today, a mother facing punishing poverty still takes the time to teach her child, scrapes together what few coins she has to send that child to school -- because she believes that a cruel world still has a place for that child's dreams.

Let us live by their example. We can acknowledge that oppression will always be with us, and still strive for justice. We can admit the intractability of depravation, and still strive for dignity. Clear-eyed, we can understand that there will be war, and still strive for peace. We can do that -- for that is the story of human progress; that's the hope of all the world; and at this moment of challenge, that must be our work here on Earth.

Thorbjørn Jagland, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, also reiterated this tension in his speech yesterday.

The Committee knows that many will weigh his ideals against what he really does, and that should be welcomed. But if the demand is either to fulfil your ideals to the letter, and at once, or to stop having ideals, we are left with a most damaging division between the limits of today's realities and the vision for tomorrow. Then politics becomes pure cynicism. Political leaders must be able to think beyond the often narrow confines of realpolitik. Only in this way can we move the world in the right direction.

I don't share this to defend Obama's decision on Afghanistan. Niebuhr himself was never easily pigeonholed - supporting the Cold War but being adamantly against the US policy in Vietnam and perhaps one of the first in this country to criticize American exceptionalism with its negative impact on our foreign policy. His message seems to be that we have to enter these conversations individually with humility about the limits we all have as humans in an imperfect world with the capacity for real evil.

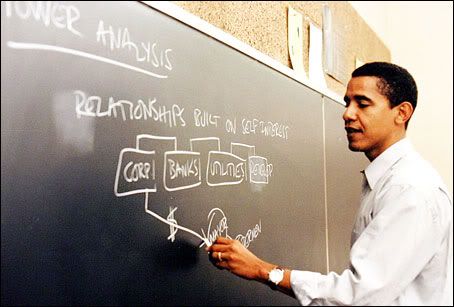

Some of you might remember this picture of Obama from his days as a community organizer.

Obama not only studied Niebuhr, he was schooled in the thinking of Saul Alinsky who, interestingly enough, required all of his students to read Niebuhr. What all three men share in common is this understanding of the power our idealism must challenge and the risks associated with wielding power in return. And yet, they all also agree that we can't shy away from our ideals. Living with that kind of tension means that our vision is almost never perfect. And yet it is exactly why we have to constantly see the world through both eyes.

Well said Nanc, liked it a lot.

ReplyDelete